This article is written by Syed Ameer Hussain.

To Turkey as Principal Pakistan Study Group Ankara – 16, June 2025

“I want to die at this place.”

Part-1

In the meantime, I had spent 26 years at Aitchison, a place that had become more than just my workplace; it was home. Every brick of the campus, every whisper in the corridors, every tradition felt like a part of me. But, as all journeys do, mine too seemed to be approaching a turn I hadn’t planned for. My time, it seemed, had come to an end.

One morning, while flipping through the newspaper over a quiet cup of tea, an advertisement caught my eye. It was for the position of Principal at the Pakistan Embassy Study Group in Ankara, Turkey. I glanced at it, pondered for a moment, and then let it go with a shrug, the salary was modest, hardly enough to tempt me away from all that I had built and loved at Aitchison.

A week later, the Principal called me into his office. His expression was unreadable. He said, quite directly, “I want you to go to Turkey.”

I smiled faintly and replied with a touch of sarcasm, “Do you want me to edge out of Aitchison?”

Iran’s State TV Under Israeli Attack

A 113 Km-Long Canal: Inside India’s Big Indus Waters Treaty Plan

For more such Opinions & Blogs, click here.

His response came without a trace of humor — and without a question. He simply said, “Now that you have seen all aspects of Aitchison’s administration, it would be better for you to go and gain some experience outside. That way, you can come back as a Headmaster — or even the Principal.”

I was taken aback. My heart resisted the idea. “But sir,” I said quietly, “I want to die at this place.”

He didn’t indulge my sentiment. He cut the conversation short with a finality that told me there was no room left for protest. “The Ambassador is coming today to conduct interviews. I want you to sit for it.”

I made one last attempt, clinging to the practical side of the matter. “I saw the advertisement,” I said, “but the salary… it’s meagre.”

He didn’t miss a beat. “If he takes my man,” he said with calm certainty, “he’ll have to raise the salary by the way I have already talked to him. He has agreed to raise 500 dollars.” I smiled and left.

That afternoon, I sat in the principal’ waiting room, waiting for my turn to come. My mind was divided — one part still roaming the playing fields and classrooms of Aitchison, and the other trying to prepare for a future I hadn’t chosen. I wasn’t nervous, but I wasn’t eager either. It felt like I was watching someone else’s life unfold in front of me, and I was simply an actor following directions.

The Ambassador was sharp, articulate, and wasted no time getting to the point. The questions came one after another — about leadership, curriculum development, school culture, diplomacy in an academic setting. I answered as best I could, speaking from the heart, drawing on my decades at Aitchison. There was no pretense, just truth — the kind you gain from long years of service, of watching young boys become fine men under your care.

He listened intently, occasionally nodding, sometimes smiling. Then, toward the end, he put down his pen and said, “We don’t just need a principal. We need someone who can build a legacy. Someone who understands tradition but isn’t afraid of change.”

I wasn’t sure if I was the man he was describing, or if I even wanted to be, but I nodded respectfully. The interview ended, and I walked out of that room not knowing whether I was walking into a new opportunity or leaving behind everything I had ever worked for.

And then, quite unexpectedly, the very next day, our world shifted.

The Principal himself arrived at our home, a rare and somewhat unsettling event. My wife and I exchanged puzzled glances as he stepped into our modest living room, his face a mixture of excitement and gravity. Without much preamble, he turned to my wife and declared, almost dramatically, “Begum Sahiba, the Ambassador has fallen in love with your husband. You should start preparing to go to Turkey.”

For a moment, time stood still. I stared at him, unsure whether I had heard correctly. My wife blinked in disbelief. Turkey? Us? It sounded like something out of a novel.

Iran urgently signaling to Israel and US that it wants talks, end to hostilities: WSJ

Three injured in mysterious blast during reconstruction of mosque in IIOJK

“We were shocked,” doesn’t even begin to describe it. Bewildered, overwhelmed, and more than a little skeptical, we listened as he went on. “You’d be fools to decline this offer,” he said, his voice low but insistent. “Opportunities like this don’t come knocking twice. Most people spend their whole lives waiting for such a chance and here it is, served on a silver platter.”

As he spoke, details unfolded: the salary had been raised, accommodations arranged, everything pointing to a life-changing move. It was as if the universe had reached down and plucked us from the ordinary, nudging us toward an unknown future. My heart pounded with a mix of fear and excitement. Was this real? Was I truly about to leave the familiar halls of Aitchison, the same hallways I had walked for years for a new life in a foreign land?

And then, a memory hit me like a jolt of lightning.

Just two months earlier, a man had come to me, a teacher looking for a job, sent by a colleague of mine. He seemed unremarkable at first, until someone mentioned his curious talent: he could read palms, they said, could interpret the lines etched on your hands with eerie precision. I had laughed it off, of course, superstition wasn’t really my thing. But for fun, I let him take a look at my hand.

What he said chilled me.

He squinted at my palm, traced a finger along one of the lines, and then looked up, eyes wide. “What are you doing in Pakistan?” he asked, genuinely puzzled. “You’ll be out of this country before the year is over.”

I had laughed it off as a joke, surely. Nothing more than a good story to share over tea.

But now, with the Principal’s words still echoing in our home, and the Turkish offer shimmering before us like a mirage turned real, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up.

Lo and behold, how true his words turned out to be.

It was as though fate had been quietly working behind the scenes, setting the stage for a plot twist I never saw coming. And just like that, a new chapter beckoned, not only across borders but perhaps across destinies.

A week later, the letter arrived: I had been selected. The salary had been revised, as promised. The position was mine should I choose to take it.

That night the family sat at the dinner table in silence for a while. Then my son said, “You always told us to embrace change when it’s time. Maybe this is your time.” I didn’t respond, but I smiled the kind of smile that carries both pride and sorrow.

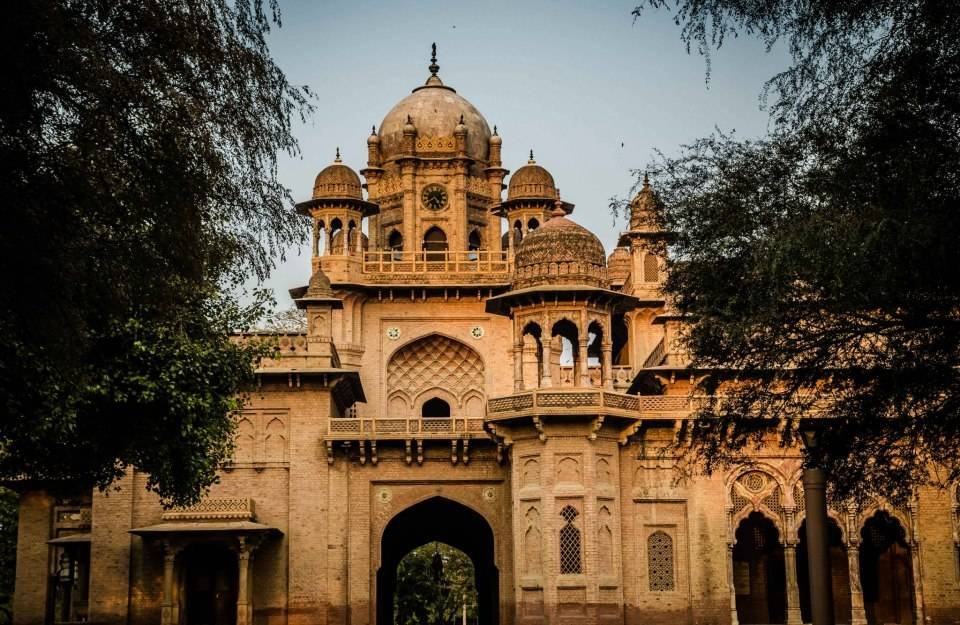

Leaving Aitchison wasn’t just leaving a job. It was leaving behind an era of my life. I took one last walk across the grounds before my final day: past the Main Hall, the iconic old building, under the canopy of pipal avenue, along the cypress avenue, along the cricket fields where generations of students had cheered and competed. I paused at the mosque, then made my way to the boarding houses where I had once served as housemaster—first of Kelly House, then Godley House. I stood there for a long while, lost in thought. Eventually, I walked over to the bench in front of Godley House, the place where my journey at Aitchison College truly began, and sat in quiet reflection, memories flooding back as I mused over the years gone by.

I wasn’t just saying goodbye to buildings. I was parting from memories, from countless handshakes, from the echo of young laughter in the corridors, from the quiet pride of knowing I had helped shape lives.

War only option if India blocks Pakistan’s water, says Bilawal

India deploying 580 more paramilitary companies in IIOJK

Then, with a suitcase in one hand and hope in the other, I boarded the flight to Ankara. A new land. A new role. A new chapter.

But a piece of Aitchison, the heart of it, traveled with me.

Ankara a Diplomatic City – But with a Heart

Part – 2

Ankara greeted me not with fanfare, but with a quiet sense of purpose. It was a city of diplomats and green hills, where the air carried both the chill of high altitude and the formality of foreign service. The Pakistan Embassy School was nestled modestly close to the diplomatic enclave — a school small but tall in size, carrying the weight of representing an entire nation abroad.

My first morning there, I stood outside the school gate before sunrise, watching the Turkish sky shift slowly from grey to gold. The school was still locked, the corridors silent, yet I felt an odd calm, as if I was meant to be there, even if I hadn’t asked for it.

The transition was not easy. Gone were the grand traditions and sprawling campus of Aitchison. The building rose tall, reaching up to six storey, with a staircase that wound upward like the spiral stairs of a minaret, the resources were limited, the staff a patchwork of expatriates and locals, and the students, children of diplomats, military attachés, and overseas workers were transient, often changing schools every few years. There was no house system, no prefects in blazers marching to assembly. There was no heritage to preserve only a school to build. But perhaps, that was the gift.

I got to know every student by name. I made it a point to be there at the gate each morning, to shake hands, to look them in the eye and remind them they mattered. We held our first sports day that year in a borrowed Turkish school ground, graciously made available through the courtesy of our ever-smiling, always helpful military attaché, we organized a memorable sports event start of sports competition. The students wore Pakistan’s green and white like a badge of honour. For many of them, it was the first time they felt a genuine connection to the country of their parents.

We also reached out to METU University, known for hosting India’s Independence Day celebrations annually—a popular event on campus. We decided to celebrate Pakistan Day, 23rd March, there. The children and their parents prepared with great enthusiasm, and their hard work paid off. The event was a great success, well-received by the university students and faculty alike.

As part of the celebrations, we arranged a friendly cricket match between the embassy officials and members of the Pakistani community living in Ankara. It was a lively, spirited affair and contributed to the overall success of the day.

Naseem Shah has no place in the team based on merit

“Tehran Residents Will Soon Pay The Price”: Israel’s Big Warning For Iran

The following evening, the embassy hosted a formal dinner for ambassadors from various countries. Since it was our national celebration, I wore the Sherwani I had tailored during my time as Housemaster of Kelly House, proudly pinning a small Pakistani flag to it. Many of the embassy staff had their children enrolled in our school, which gave me a certain prominence at the gathering. The ambassadors greeted me warmly, and our own ambassador, in good humour, joked that I should stand in the back row, I was attracting more attention than he was!

It wasn’t just a school it was a small embassy of values, of hope, of continuity. I called it a Mini UNO.

But perhaps what moved me most was how I grew in that time, not just as an educator, but as a human being. Living away from my homeland, navigating a multicultural environment, dealing with bureaucracy and diplomacy, and leading without the cushion of legacy; it sharpened me. It humbled me.

There were moments of deep loneliness. I often wished my family could be there with me. I knew how much my children would have enjoyed the school and the warmth of this welcoming new country. I would have certainly brought them over, but the absence of O Level and A Level programs made it impossible, both my children were enrolled in those crucial stages of their education. I was entitled to a family ticket, which made the prospect all the more tempting, and my accommodation in the diplomatic enclave was spacious and well-suited for a family. Yet, despite the comfort and opportunity, their education had to come first.

I felt a deep sense of responsibility, almost a sacred obligation, to lay the groundwork for starting O Level classes at our school. It was not just an academic expansion; it was a step toward giving our students broader horizons and internationally recognized qualifications. The idea had the full support of our ambassador, who personally tasked me with initiating the process. With his encouragement and backing, I set out to connect with Cambridge University, the institution responsible for the administration of the O Level examinations.

However, what I imagined would be a straightforward administrative task soon turned into a monumental challenge. Reaching the right department at Cambridge was nothing short of a Herculean effort. The initial calls were met with long waits and repeated redirections. Each connection felt like a small victory, only to be followed by the frustration of being transferred yet again or placed on indefinite hold.

The principal’s secretary, who was assisting me, would often spend hours waiting on the line, only to be told that the concerned officer was either unavailable or out of the office. On more than one occasion, we managed to get through to the right person, only to be told to call back another time. It felt like an endless loop, time zones, formalities, and layers of administration all conspired to stall our progress.

Woman Threatens Petrol Pump Staffer With Revolver

UK appoints first woman to head MI6 intelligence service

Eventually, after weeks of futile calls and unproductive correspondences, it became clear that the only real solution was a direct one. It was decided that I would travel to Cambridge myself and handle the matter in person. Though this meant temporarily stalling the programme, it was a necessary delay. Sometimes, progress demands more than perseverance, it demands presence. And I was determined not to let red tape stand in the way of what I knew could be a transformative opportunity for our students.That Fateful e-mail from Home

Part – 3

I had been in Ankara long enough to leave their mark on me, the crispness of its winters, the golden hush of autumn leaves on campus, the sudden bloom of cherry blossoms after a hard frost. I had built a life around the rhythms of a foreign land, and in many ways, it had been good for me. The work was meaningful, the people warm in their own reserved way, and the city dignified with a quiet grandeur. But beneath the polished surface of my days, something had begun to stir. A slow disquiet. A kind of longing I hadn’t felt in years.

It began subtly, a craving for the sound of Urdu spoken casually on the street, the scent of chai infused with cardamom wafting through open windows, the loud, chaotic symphony of a Karachi market, or the dignified hush of Lahore’s old bookshops. I began to miss the familiar imperfections of home. The spontaneous laughter of friends, the way elders would place a hand on your shoulder mid-conversation, grounding you. Even the chaos, no, especially the chaos, began to feel like something I needed to feel alive again.

I missed my family. I missed the ease of speaking without translating in my head. I missed the feeling of belonging, not because I was useful, but because I was known.

And then, as if fate had been listening to my unspoken yearning, the e-mail arrived.

It was not grand, no formal preamble, just a plain e-mail with the understated logo of the Infaq Foundation in one corner. But when I read it I felt as if something inside me exhaled. It was an offer, brief and direct, inviting me to join the Foundation in Karachi. No persuasion, no embellishment. Just an open invitation. But it read like more than a professional proposal.

It felt like home was reaching out across continents, saying, Come back. We need you. You’re ours.

Though Karachi wasn’t my city by origin, it suddenly felt like the city of my return. It wasn’t about geography. It was about resonance. A sense of purpose that aligned with my roots. Most of my relatives lived there.

Delhi-bound Air India flight returns to HK after mid-air technical issue

US Embassy in Israel sustains minor damage after Iranian missile strike

By that time, I was no longer the young man who had once dreamed wide-eyed beneath the canopies of Aitchison’s majestic trees. Living in Ankara had been a crucible. I had shaped a school there, not just with policies and plans, but with care, discipline, and relentless reflection. I had matured in silence, without applause. I had learned to lead without a shared cultural shorthand. I had felt the loneliness of command, but also its quiet strength. I had been tested, in patience, in adaptability, in my sense of identity, and I had emerged, not unscathed, but unmistakably seasoned.

Still, underneath the layers of experience, I was the same man who had once stood barefoot on the lawns of Lawrence College, inhaling the pine-scented air, or walked proudly down the corridors of Aitchison, heart swollen with a sense of belonging. I was the same man who had once said, perhaps too dramatically, “I want to die at this place,” believing that legacy could live in the soil beneath one’s feet.

That memory returned with force as I stood holding that letter, the soft Ankara sunlight filtering through my bedroom window.

This was my moment of return. Not just a return to Pakistan, but a return to self, to purpose, to place, to people. I would go not as an exile coming back, but as a man who had gone out to learn, and now returned to serve.

So, I folded the e-mail carefully and placed it on my desk. I stepped outside, breathing in the foreign air that had taught me so much, and I whispered a quiet farewell to Ankara, not of regret, but of gratitude.

My journey back had begun.

Lahore—The City That Waited

The plane began its descent over Lahore just as the early morning light broke over the horizon. Through the small oval window, I could see the city slowly emerging, a patchwork of rooftops, minarets catching the golden light, and that unmistakable haze that sits like a quiet shroud over the city each dawn. My heart tightened.

It wasn’t just a return. It felt like a reunion — the kind that happens not just after distance, but after change.

When I stepped off the plane, the first thing that struck me was the warmth — not the heat, though Lahore never spares you that — but the human warmth. The language that hit my ears, the accents that curled around words like old friends, the pace, the sounds, even the chaos of the arrivals lounge — it all felt like a living embrace.

I wasn’t just back in Pakistan. I was back in Lahore, a city that had shaped me long before I knew I was being shaped.

There was no official reception. No garlands. Just my family waiting at the gate with their signature half-smiles and a quiet, knowing look in their eyes. They didn’t say much. They didn’t need to. Sometimes home doesn’t speak in words; it speaks in gestures, in silence, in memory.

As we drove through the roads, the city unfolded before me like an old photograph slowly coming into focus, familiar but aged. The Mall Road still stood proud, lined with colonial architecture now dulled with time but never dignity. The bougainvillea still spilled over crumbling boundary walls in chaotic bursts of colour. The rickshaws still honked like they owned the road. And somewhere in all of this, I felt a curious sense of stillness. As if Lahore had been waiting for me. Not impatiently, but faithfully.

We drove past the gates of Aitchison College.

Iran wants to kill Trump, plotted assassination: Netanyahu’s explosive claim

Sonia Gandhi Admitted To Delhi’s Ganga Ram Hospital

For a moment, time dissolved. I saw myself again, a younger version, walking with long strides and borrowed confidence. I could almost hear the shouts on the cricket ground, the clang of the bell echoing through the corridors, the heady mix of discipline and dreams.

I didn’t stop. I didn’t need to. Seeing it was enough — a silent vow had been fulfilled: I had come back to the soil where my roots were buried.

Later that day, I sat quietly in the veranda of my family home, a glass of cold water sweating on the side table, the scent of jasmine drifting in from the garden. The ceiling fan turned lazily above, as if in no hurry. And neither was I.

After so many days, where every conversation had to be weighed, where I constantly walked the tightrope between cultural diplomacy and institutional discipline, I could finally exhale. Not because everything was perfect here. It never had been. But because here, I didn’t have to explain myself. I belonged by default, not by performance.

Lahore had welcomed me not with fanfare, but with familiarity. And perhaps that’s all I needed.

The next chapter would begin soon, Karachi, Infaq Foundation, new challenges, but for now, I let Lahore hold me. Not as a visitor, not as a returnee, but as one of its own.

The next morning, I walked through the familiar corridors of Aitchison College, the soft rustle of trees and the echo of boys’ laughter in the background, sounds I had grown used to over the years. But this time, something felt different. I was not just returning from a weekend or a holiday, I was walking towards closure.

I went straight to the Principal’s office, the same one who had once asked me a pointed question during my interview years ago, a question that lingered with me through my journey at the school. He looked up as I entered, perhaps sensing from my expression that this wasn’t a routine visit.

“Sir,” I began, my voice calm but resolute, “I’ve come to say that it’s time for me to move on. I have seen dollars now,” I added with a faint smile, alluding to the modest savings I had gathered from my recent overseas assignment. “My children will soon be entering university, and I need to prepare for that—both financially and emotionally. You see, I want to explore the world of Pakistan now. There are new roads for me to travel, different dreams to chase. And since I’m not allowed to teach tuitions here, I have no choice but to leave Aitchison permanently.”

There was a pause—brief but heavy with unspoken memories. He looked at me, a man who had once arrived full of ideals and ambitions, now making a difficult, conscious decision to let go. The conversation didn’t last long. He nodded, a glint of understanding in his eyes.

“Fine,” he said, “I wish you the best of luck.”

And just like that, it ended. No long goodbyes, no dramatic speeches. But as I stepped out of his office, I carried with me a decade of growth, struggle, friendship, and quiet triumphs. I wasn’t just leaving a school, I was stepping into the next chapter of life, carrying with me the lessons of one of the most prestigious institutions in the country, and the quiet dignity of a teacher choosing his path.

For more such Opinions & Blogs, click here.

Saudi Flight With Hajj Pilgrims Lands Safely In Lucknow After Technical Snag

‘No Landing Permission’: Hyderabad-Bound Lufthansa Flight Returns To Frankfurt Mid-Air

Kirsten Blames PCB For Pakistan Cricket’s Downfall

This article is written by Syed Ameer Hussain.

Stay tuned to Baaghi TV for more. Download our app for the latest news, updates & interesting content!